The Ethics of Medical Assistance

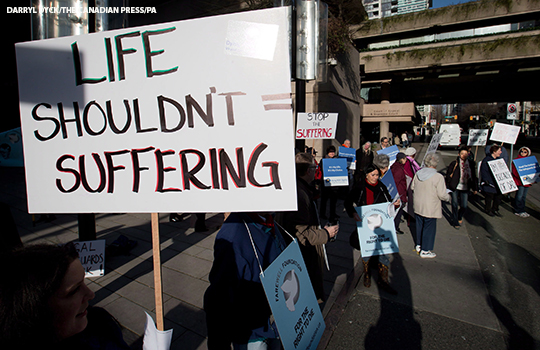

People demonstrate outside the B.C. Court of Appeal during a hearing into the federal government’s appeal of the B.C. Supreme Court ruling that struck down the laws making physician-assisted dying illegal, in Vancouver, B.C., on Monday March 4, 2013. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

March 24, 2022

Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) is legal in 10 states in America for patients with terminal illnesses who wish to pass on their own terms. Last year, Canada legalized medically assisted suicide for patients with psychiatric disorders, which are defined as mental illnesses diagnosed by a professional. This new law will go into effect in March of 2023. This practice has been enacted in several countries prior to Canada, such as the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

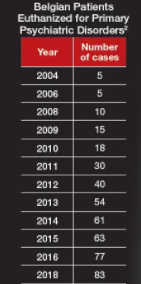

Belgium, one of the first countries to legalize MAID for psychiatric disorders, shows that a patient is eligible for assisted dying if their illness “could not be treated according to acceptable means,” according to the Psychiatric Times. These cases are rare but have been steadily increasing since the law was passed in 2002.

Canada’s initial law, allowing medical euthanasia for only patients with a terminal illness, was rather undefined in general terms. It stated that a patient’s death must be reasonably foreseeable, but failed to define a timeline and other specifics. This original bill was passed in 2016. Between its passing and November 2020, 13,000 Canadians had been voluntarily euthanized. Not much later, in 2021, a Quebec Superior Court ruling challenged the restrictions of the bill. In turn, a new bill was proposed allowing non-terminal illnesses, including psychological ones deemed untreatable, eligible for more patients with fewer restrictions – – making patients struggling with mental illness fit for voluntary euthanasia.

Here are a number of requirements for Medical Assistance in Dying: a patient must be over 18, made the request willingly, and is in “an advanced state of irreversible decline that causes extreme suffering,” according to Al Jazeera, a worldwide news organization.

Naturally, the passing of this law leads to a difficult discussion: Is medically assisted suicide ethical?

There is strong support for the law, including advocates for mental illnesses and psychiatric organizations in particular. Adam Maier-Clayton, a man with several disorders including chronic depression and severe Somatic Symptom Disorder, which is a psychiatric disorder causing physical pain, was one of the most influential advocates for the bill. His YouTube channel, where he told his story, quickly gained controversial attention. He was very direct in his thoughts, even entitling one video “I have a mental illness, let me die.” Maier-Clayton killed himself in 2017. The argument for the law, the argument made by Maier-Clayton, is that psychiatric disorders are just as serious and debilitating as physical ones, and should be treated accordingly.

Canadian Senator Stan Kuchen signed off on the bill and believes that people struggling with mental illnesses deserve the right to make their own decision. He argues, “It is not for us to decide if a person’s disorder is intolerable to them.” Dying with Dignity Canada responded to Kuchen’s sign-off, calling it “a momentous day for end-of-life rights in Canada.”

However, there is possibly a larger group heavily against the law allowing eligibility due to mental illness. The World Medical Association finds Medical Assistance in Dying “fundamentally incompatible with a physician’s role as a healer.” This brings the counterargument that it is unjust to expect doctors and psychiatrists to assist in ending a patient’s life. For the cases of mental illness, psychiatrists would be tasked with a life or death decision for their patients, as they would be in charge of which suicides are deemed acceptable. They would be expected to prescribe a deadly dose of medication to end a patient’s life.

However, there is possibly a larger group heavily against the law allowing eligibility due to mental illness. The World Medical Association finds Medical Assistance in Dying “fundamentally incompatible with a physician’s role as a healer.” This brings the counterargument that it is unjust to expect doctors and psychiatrists to assist in ending a patient’s life. For the cases of mental illness, psychiatrists would be tasked with a life or death decision for their patients, as they would be in charge of which suicides are deemed acceptable. They would be expected to prescribe a deadly dose of medication to end a patient’s life.

John Meyer, a psychiatrist from Ontario, comments on behalf of a majority of psychiatrists, stating “We now have patients who are asking us to stop treatment – patients who will get better – because they don’t have to keep trying anymore.” Mark Sinyor, a psychiatrist and previously vice president of the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention, is also concerned. He fears that while the law states a person’s state must be “irredeemable” in order for them to be eligible for MAID, is worried that there is no concrete way to define an illness as irredeemable.

Psychiatrist Sephora Tang adds that “patients could be approved for MAID without any assurance that they have received adequate support or care,” according to Psychiatric News. This is another large concern, as it is difficult to decide if a patient’s condition is truly untreatable. The law is as poorly defined as the original bill built specifically for physical illness, putting an unrealistic and unjust amount of pressure on psychiatrists.

It seems that although patients who are suffering being able to make their own decision is a worthwhile argument, it is unfair to ask doctors and psychiatrists to partake in ending lives when they have dedicated themselves to saving those very lives.